Open Letter on Public Record · Winnipeg, Manitoba

·

WPS Let Seal Expire During Investigation. The CBC Went Live. The Outcome Never Did. Despite multiple arrests, a City of Winnipeg employee was never charged, and the public record was left structurally incomplete.

This letter uses primary sources, the original CBC reporting, the CBC Ombudsman’s review, released police production orders, personal correspondence, and a Manitoba Prosecution Services letter, to correct an incomplete public record and demand accountable, outcome-focused clarity.

Outcome (undisputed)

- No criminal charges were authorized to be laid

- No trial occurred

- No conviction or judicial finding of wrongdoing

- No civil action was commenced

These facts represent the final disposition of the investigation.

Quick index / glossary

A short list of definitions to keep this letter readable for non-specialists.

- COW

- City of Winnipeg, the municipal government and employer referenced in this letter.

- WPS

- Winnipeg Police Service, the municipal police force responsible for investigating alleged criminal offences in Winnipeg.

- Crown

- The prosecuting authority representing the state. In Manitoba, this function is carried out by Manitoba Prosecution Service under Manitoba Justice.

- MBPS

- Manitoba Prosecution Service, the Crown office responsible for reviewing investigations and authorizing criminal charges in Manitoba.

- ITO

- Information to Obtain — sworn materials submitted by police to a judge to seek judicial authorization for certain investigative powers.

- Production order

- A court order compelling the production of specified records (such as workplace emails) for investigative purposes. It is a judicially authorized investigative tool, not a finding of wrongdoing.

- Sealing order

- A court order restricting public access to court records for a defined period, commonly to protect the integrity of an ongoing investigation.

- Arrest

- A police action that temporarily deprives an individual of liberty on suspicion of an offence. An arrest does not require charges to be authorized and does not imply guilt.

- Promise to Appear

- A document requiring a person to attend court at a future date. It can be issued in connection with an investigation and does not, by itself, mean charges have been laid.

- Charges authorized

- A decision by the Crown approving criminal charges to proceed. This is legally distinct from an arrest, investigation, or police expectation of charges.

- Charges laid

- The formal act of swearing an information before the court to commence a criminal prosecution. Charges are typically laid only after Crown authorization. If charges are not laid, no criminal court process occurs.

- CBC

- Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, Canada’s public broadcaster.

- JSP

- Journalistic Standards & Practices, the CBC’s internal editorial policies governing accuracy, fairness, and responsible reporting.

- FIPPA

- Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (Manitoba), legislation governing access to government records and the protection of personal information.

Executive Summary

This open letter documents a public-record failure arising from a Winnipeg Police Service investigation and related media coverage. In 2019, a City of Winnipeg employee was publicly named and arrested during an ongoing investigation, yet no criminal charges were ever authorized, no trial occurred, and no civil action followed.

While such arrests may be lawful, the absence of any durable, prominent, public explanation or outcome record has left an incomplete and misleading public narrative. This letter seeks outcome-level clarity, proportional accountability, and a public record that reflects conclusions as clearly as it once reflected allegations.

Background

On February 25, 2019, CBC News published a story naming my father, City of Winnipeg employee Ed Richardson, and allegations of fraud. The article remains publicly accessible today: City of Winnipeg manager in charge of police radios arrested after 2-year investigation.

The public record has several facts that must be as easy to find as the headline: No criminal charges were ever laid. There was no trial, no conviction, and no judicial finding of wrongdoing. No civil action was ever initiated. Those facts are not merely "context." They are the indisputable outcome.

For my family, this was not an abstract policy failure. It was years of uncertainty, silence, and reputational harm faced by not only my father, but my entire family. This is something that no official outcome ever publicly resolved.

This letter is about timing, record handling, and follow-through: investigative court material became available to media during an ongoing investigation, and a story was published at the allegation/arrest stage, and then the outcome, no charges, never received equally durable, prominent, searchable follow-up.

This letter is not only about one person. It shows how easily an ordinary citizen can be publicly branded; and how hard it is to undo that branding if the outcome is never published.

If this can happen to a long-serving public employee with union representation, documented records, and eventual institutional review, it can happen to anyone. Most people do not have the time, resources, or capacity to spend years correcting an incomplete public record. When outcomes are not made visible, allegations become permanent, regardless of the truth.

If investigative records can become public mid-investigation, if arrests can occur without charges being authorized, and if outcome reporting is optional rather than mandatory, then any person who works in the public or private sector can find themselves permanently defined by an allegation that was never proven to hold any merit.

What this letter is asking for

- A public record that states “no charges” as clearly as the original story stated the allegations.

- A plain acknowledgement that investigative material became releasable because a sealing order expired, and was not renewed prior to media disclosure during an ongoing investigation.

- A clear explanation of why Richardson was arrested (more than once) without charges being authorized by the Crown, what investigative purpose was served, and what changed (if anything) between arrests.

- A clear explanation of why a Winnipeg Police Service spokesperson is quoted by the CBC as having stated that the investigation was “complete,” when released police records indicate that further investigative steps were taken after this statement.

- A durable CBC follow-up outcome update to the original article, not merely a minimal note, consistent with the Ombudsman’s stated expectation of more comprehensive reporting at conclusion.

- For CTV News (Jeff Keele) and the Winnipeg Free Press (Carol Sanders) to add a visible outcome update to their original articles, clearly stating that the investigation concluded with no criminal charges laid and no civil action initiated.

Timeline: the record of what happened

The dates below are the spine of this letter. They show how a sealed investigative record moved into public reach, how media contact and arrests followed, how a WPS spokesperson claimed the investigation was complete, how the story aired, and how a second production order was later sought, all while the outcome remained “no charges,” and no civil action.

Key dates

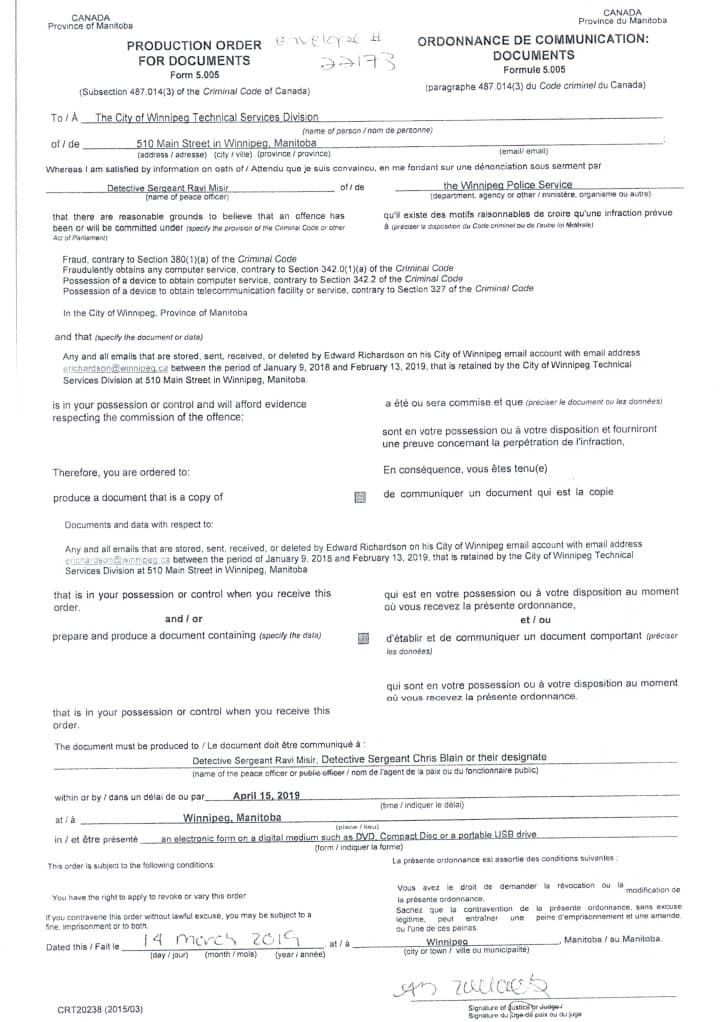

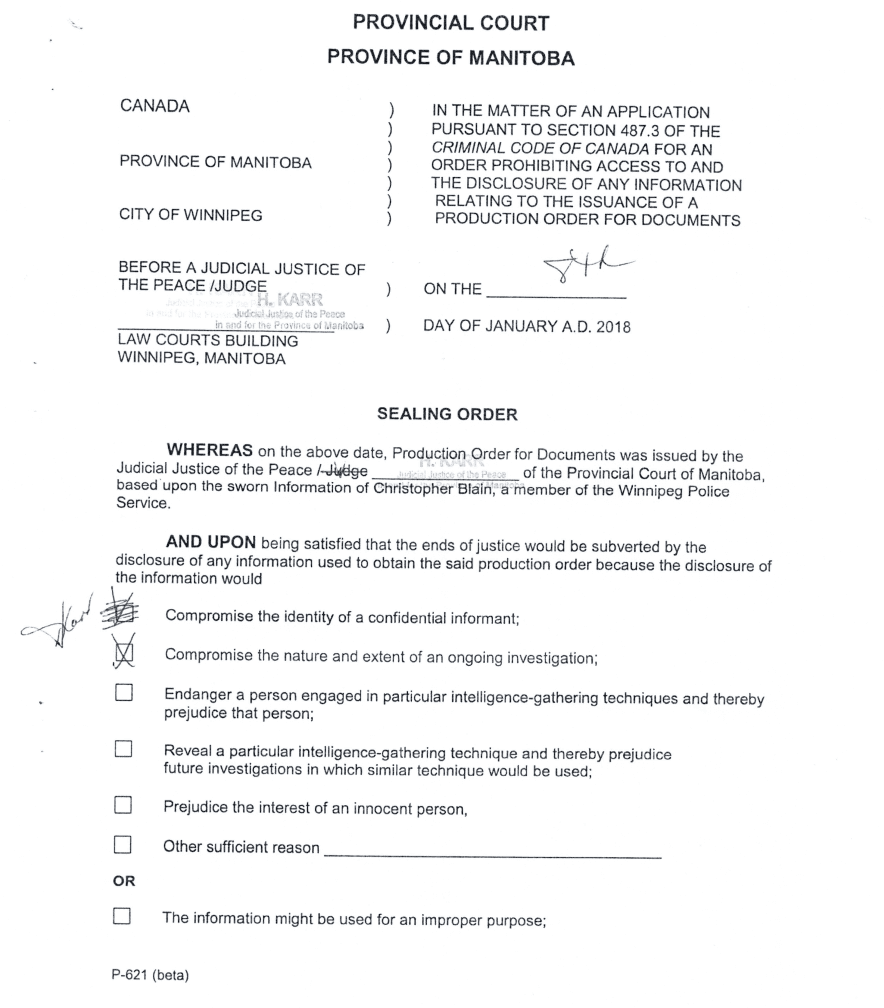

- Jan 8, 2018: WPS D/Sgt. Chris Blain requested a production order for Richardson’s work emails; it was granted, and sealed for a one-year period to protect an ongoing investigation.

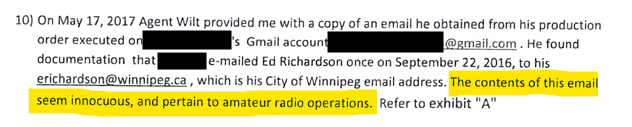

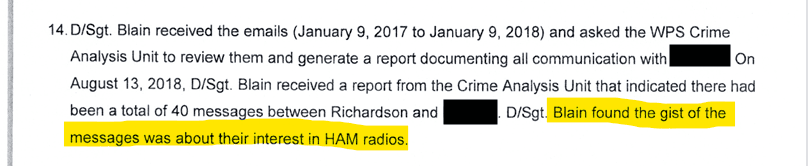

- Aug 13, 2018: Blain received a report from the Crime Analysis Unit that indicated there had been a total of 40 messages between Richardson and another individual. D/Sgt. Blain found the gist of the messages was about their interest in "HAM radios" (amateur radio was a mutual hobby of both individuals).

- Jan 9, 2019: The production order became unsealed as the WPS did not renew the sealing order prior to its expiry, and it became available to be requested by media.

Context (Unrelated Proceeding)

In an unrelated judicial proceeding on January 9, 2019, Ms. Barghout, on behalf of CBC, requested copies of a number of other unsealed production orders and their ITOs.

The Attorney General of Manitoba opposed disclosure, citing risks to innocent persons, the fact that no charges had been laid so the ongoing investigation needed to be protected, and the presence of sensitive personal information in those materials.

Reference: CBC v Canada (Attorney General), 2019 MBPC 59, para. 73

- Jan 25, 2019: CBC's Caroline Barghout received the unsealed January 2018 production order / ITO for Richardson's work emails.

- Later: WPS attempted to seal the production order again, as the investigation was still ongoing, but the application was denied. The records had already been disclosed to media.

- Feb 8, 2019: Barghout contacted Richardson during the police investigation. Barghout read the entire 12-page police document to him over the phone, prior to police ever questioning Richardson regarding this matter.

- Feb 9, 2019: Richardson voluntarily attended WPS headquarters to try to understand what was going on, he did not feel the need to have a lawyer present at the time; Richardson was arrested for Fraud over $5,000, Unauthorized use of a computer, and Possession of a device to obtain unauthorized use of a computer and released without charges.

- Feb 13, 2019: Richardson was placed on administrative leave.

- Feb 21, 2019: Richardson was told by WPS that he was going to be charged. At the advice of legal counsel, Richardson voluntarily surrendered himself and was arrested again, this time for Fraud Over $5000, Fraudulently Obtains Any Computer Service, Possession of Device to Obtain Computer Service, Possession of Device to Obtain Telecommunication Facility or Service, and issued a Promise to Appear for a person not yet charged with an offence. Richardson was scheduled to appear in court where charges were expected to be laid on Apr 2, 2019.

- Feb 25, 2019: CBC published the article written by Caroline Barghout, deviating from the JSP's default policy by publicly naming Richardson prior to any charges being laid. This coverage was then repeated by other news outlets the same day, who also publicly named Richardson prior to charges.

- Feb 27, 2019: Richardson was terminated from his 21-year position at the City of Winnipeg. Following this termination, Richardson and the union initiated the grievance process.

- Mar 14, 2019: Weeks after both arrests, and a WPS spokesperson was quoted as saying the investigation was “complete” and charges were expected, WPS Detective Sergeant Ravi Misir filed another production order for Richardson’s work emails as part of the same ongoing investigation into the fraud allegations. This investigative step was never reported on. This sworn statement to the court shows Misir was still searching for evidence of knowledge and intent supporting the offences, and states they were trying to make the evidence more probative to be able to prove the offences in a prosecution.

- Apr 2, 2019: No charges were laid on the scheduled court date.

- Jun 2020: Manitoba Prosecution Services formally decided not to proceed with any charges in this matter. The legal matter concluded with no charges, no trial, and no judicial finding of wrongdoing. No civil action was ever initiated against Richardson.

- Jan 2021: Richardson’s termination from the City of Winnipeg was grieved by his union under the collective agreement and scheduled for arbitration. The grievance concluded prior to arbitration. The conclusion took the form of a confidential settlement. Out of respect for confidentiality obligations, this letter does not describe or characterize the terms of that settlement.

If institutions believe any of the above needs nuance, they should provide it publicly. This is precisely what an accountable record looks like: specific dates, specific actions, and a clear outcome.

The outcome that must be stated

No charges were authorized to be laid

“The Department can advise that although a court date was designated in this case, no charges were authorized to be laid”

Official outcome statement

“As you know, no charges were laid in this matter.”

When allegation-stage reporting is widely disseminated, the absence of equivalently prominent outcome reporting results in an incomplete public record. With an absence of charges, the ethical burden shifts from “what happened?” to “what was proven?”, and the answer is: Nothing was proven. None of the allegations were proven in court, or anywhere else.

Published during an ongoing investigation, before any court outcome existed

At the time the CBC article was published on February 25, 2019, the police investigation had not concluded, no charges had been authorized by the Crown, and no court outcome existed. Prior to publication, the reporter contacted Richardson regarding the investigation before police had questioned him.

The lead investigator for the case, WPS Detective Sergeant Chris Blain, described a lengthy investigation that began in 2017, and continued even after arrest powers were exercised.

The case's lead investigator confirmed investigation was still ongoing after arrest

“It was a lengthy investigation that began in early 2017 and continued even after Ed’s arrest.”

The original CBC article quoted an unnamed Winnipeg Police Service spokesperson characterizing the investigation as "complete" prior to publication on February 25, 2019. That characterization matters, because it framed the story for readers as the conclusion of a finished investigative process.

WPS Spokesperson alleges investigation is complete

“A Winnipeg police spokesperson said its investigation is now complete and Richardson is expected to be formally charged during a court appearance next month, when he will face a number of criminal code offences, including fraud over $5,000, unauthorized use of a computer, possession of a device to obtain unauthorized use of a computer and possession of a device to obtain telecommunication service.”

However, the investigative record shows that this characterization was incomplete. A second production order for Richardson’s work emails was sought by WPS on March 14, 2019, weeks after both arrests and the CBC's article was published. Investigative steps clearly continued beyond the date readers were told the investigation had concluded.

This discrepancy raises a narrow but important public-interest question: how an investigation could be described publicly as complete and charges expected, while further compulsory investigative powers were still being exercised, and no charges had been authorized by the Crown yet.

This second production order was an investigative act that further sought to obtain all of Richardson's workplace emails over a broad period, rather than a narrowly tailored set of communications linked to specific individuals or events. This order was seeking evidence to support the allegations described, after a police spokesperson had publicly described the investigation as complete, after multiple arrests, after Richardson had been named by the media, and before the Crown ultimately declined to authorize charges.

Taken together, these circumstances warrant careful scrutiny of whether the scope and timing of the production order reflected objective investigative necessity or investigative momentum driven by untested allegations.

If the justice process ends without charges, outcome visibility becomes a basic fairness requirement. Otherwise, the public is left with an implied conclusion that was never established in court, and the named person, and their family are left carrying the permanent burden of the allegation record.

Sealing lapse: what enabled release to media

This did not become a story because an investigation had been completed, charges were laid and a case proceeded through court. It became a story because investigative court material that was originally sealed became releasable, and once it was releasable, it could be obtained on request.

Put plainly: the seal expired and the record moved from protected to obtainable. That one transition is what made the rest possible.

Media obtained the production order

“The media applied for a copy of the production order and obtained it on January 25, 2019.”

This is not a small paperwork issue. Sealing exists to protect the integrity of an ongoing investigation and to prevent premature, disproportionate reputational harm in the absence of charges or a court finding.

When that protection lapses, one foreseeable consequence is the outcome observed here: a permanent allegation record without an equally durable outcome record.

Who owned the sealing responsibility

“The seal expired” is not a force of nature. Maintaining a seal is driven by police action, not Crown initiative, and not media.

The January 2018 production order obtained by Winnipeg Police was accompanied by a sealing order, restricting public access for a one year period, to protect the nature and extent of an ongoing investigation.

Who renews a sealing order

“Before a sealing order expires, police may apply for a new one if necessary.”

Who does not renew it

“The Crown does not seek extensions…”

The WPS tried to apply for a new sealing order for these documents after the original sealing order had expired.

Attempted re-sealing after expiry

“After the sealing order had expired police applied for a new sealing order. However, that application was denied by the Judicial Justice of the Peace. Disclosure had already been made to the media by the time the application was made.”

That means the accountability question is specific: why the seal in an ongoing investigation was not renewed prior to expiry in a matter where the WPS would reasonably have understood that release could trigger publicity, permanently brand a named person, and create irreversible harm in the absence of charges?

Public trust depends not just on investigations being conducted, but on outcomes being clearly communicated. When the public sees only allegations and never outcomes, confidence in both policing and journalism erodes.

If WPS believes the public record is missing nuance (for example, internal registry processes, timing windows, or who had notice), then WPS should supply that nuance publicly; because the reputational harm has already been public for years.

How this actually unfolded, in plain language

Here is the sequence that matters, stated plainly and tied to concrete dates where possible:

- Jan 8, 2018: WPS seeks a production order for Richardson’s emails; it is sealed for 1 year to protect the ongoing investigation. A year later, the seal expires; the record becomes releasable on request despite the investigation was still ongoing.

- Jan 25, 2019: CBC obtains the unsealed ITO / production order.

- After disclosure: WPS attempts to re-seal; the application is denied.

- Feb 8-21, 2019: Barghout's contact with Richardson is followed by police contact, his two arrests and a Promise to Appear, yet no charges are authorized by the Crown to be laid.

- Feb 25, 2019: The CBC publishes their article, detailing an arrest and the investigation. A WPS spokesperson is quoted as saying the investigation was complete, and charges are expected.

- Feb 27, 2019: Richardson is terminated from his position at the City of Winnipeg.

- Mar 14, 2019: A second production order for any and all of Richardson’s work emails sent after January 9, 2018 is sought by WPS D/Sgt Ravi Misir, as part of the same ongoing investigation into the fraud allegations for which Richardson had already been arrested twice and publicly named.

- Apr 2, 2019: No charges are authorized to be laid on the scheduled court date.

- Jun 2020: Manitoba Prosecution Services decides not to proceed with any charges against Richardson. No civil action against Richardson commenced.

- Jan 2021: The grievance Richardson and the union filed concludes prior to the scheduled arbitration.

The foreseeable result is the public record we have today: the allegation moment became permanent and searchable, while the “no charges” and “no civil action” as a result, have not been made equally durable, prominent, and discoverable.

Two arrests, zero charges: the missing explanation

This is where WPS must provide accountable clarity; not investigative secrets, but basic public-interest explanation.

Richardson was arrested in connection with this matter. Charges were never authorized. When a police service uses arrest power and then the file results in no charges, the public, and at minimum the family, should be reasonably entitled to an explanation of what justified those arrests at the time, and what evidence of the alleged crimes police actually found as a result of their investigation.

Nothing in this record suggests the Winnipeg Police Service lacked the legal authority to arrest. Canadian law permits arrest on reasonable grounds even where charges are never authorized. The issue here is not legality, but typical practice and investigative purpose.

The March 14, 2019 production order that sought to obtain "any and all" of Richardson's workplace emails over a broad period, explicitly states police were still seeking these emails in an attempt at "making the evidence more probative and proving the offences in a prosecution", after two arrests, after public naming, after employment termination, and after already telling the public the investigation was complete and charges were expected.

In non-urgent, document-based fraud investigations, arrests are normally preceded by evidentiary consolidation and Crown screening, and are followed by either charges or a clear investigative outcome.

In this case, two arrests occurred without any charges ever being authorized, investigative escalation continued afterward, and no explanation has been provided as to what public-interest or investigative objective those arrests served.

That sequence may be lawful, but it does not appear to be standard procedure. It is the absence of explanation, not the existence of arrest powers, that remains unresolved.

For my family, the absence of charges did not restore what was lost or offer any accountability or closure on the matter. My father's name remained publicly associated with allegations; years passed before the matter was formally closed. The lack of a durable public outcome meant that the reputational consequences for my entire family continued long after the justice system had moved on.

After more than six years, the public record contained no outcome explanation beyond what was reflected in the original production order, and the Crown’s decision not to authorize charges.

The unreported March 2019 production order described Motorola’s update system as operating through a subscription that was held by the City of Winnipeg, while both production orders asserted a per-use financial loss based on “normal“ prices for individual refreshes.

Police claim COW held subscription for updates

“Motorola charged a fee for each update that would normally cost $94.00. The updates are called refreshes that the Radio Shop would receive through Motorola proprietary software. They were available in downloads through a subscription that the COW had.”

The document does not explain how these two positions were reconciled, whether the City exceeded any subscription-licensed entitlement, or whether any actual financial loss was proven as a result.

Contemporary media coverage relied heavily on police characterizations and estimates contained in the initial January 2018 production order, including assumptions about the number of times software updates were supposedly accessed, and those figures were then used to suggest that Richardson had obtained “millions of dollars worth of illegal software,” or was responsible for tens of thousands of dollars in loss.

This means the financial loss figures cited publicly were based on initial police estimates from this untested investigative document rather than an accurate reflection of how the system functioned in practice. These numbers were not based on any physical evidence from updated radios, or any actual realized loss determined to have taken place.

Neither production order tells us if the police found evidence of any criminal conduct in Richardson's emails, the focus of the two production orders. These documents do mention police had previously found emails that indicate an interest in amateur (HAM) radio activity, which police themselves characterized as seemingly innocuous.

This interest in amateur radios is something that was confirmed in the March 2019 production order for more of Richardson's emails following his second arrest. Here we learn what police discovered as a result of the initial January 2018 production order for Richardson's emails.

These descriptions appear in production orders sought before and after the two arrests, and before the Crown ultimately declined to authorize charges.

Under Canadian criminal procedure, the Crown’s obligation to disclose evidence arises only once an individual is formally charged and becomes an accused before the court. In the absence of charges, no disclosure obligation is triggered, and the evidentiary record remains internal to the investigative and charge-authorization process. As a result, while arrests were publicly reported, the underlying evidentiary basis was never tested in court and was never made available to the public.

What WPS can explain without compromising privacy or tactics

- What standard was applied for each arrest (e.g., reasonable grounds) and what facts supported it at the time.

- Why a second arrest was necessary (what changed between arrests, if anything).

- What date the investigation was considered “complete.”

- Whether the investigative file is currently closed, inactive, or still open, and what “closure” means in practice when no charges are laid.

- What documentation exists to summarize the investigative outcome at a high level when a person has been arrested and publicly named but no charges are authorized as a result.

This request recognizes police discretion at the investigative stage; it asks only for outcome-level explanation when that discretion results in arrests without charges.

This is not a demand for confidential evidence. It is a demand for institutional accountability proportional to the public harm. The story is public; the reputational damage is public; the absence of charges is public. The outcome explanation should be public too, at least in a redacted, high-level form.

The missing investigative outcome documentation

“No charges were laid” is the most important public fact, but it does not answer what WPS concluded, what steps were taken to close the matter, or how the system ensures a person is not left in permanent public limbo after being publicly named.

It is relevant to note a procedural distinction between search warrants and production orders (like the ones referenced in this letter) in Canadian criminal law.

Search warrants require police to file a post-execution “report to a justice”, documenting what was seized, before the details of these investigative documents can be released. This report to a justice document later forms part of the court record.

By contrast, the production orders referenced here do not require a comparable report to a justice setting out what records were ultimately produced as a result of this investigative act. As a result, unlike a search warrant, there is no automatic public record disclosing what, if anything, was obtained by police through those orders once they are unsealed.

This letter does not assume police can release sensitive investigative detail. It insists on something an accountable institution should be prepared to provide:

- A clear explanation of how sealing was monitored and why the protection lapsed in this case.

- A clear explanation of when this investigation was considered “complete.”

- A written outcome statement: no charges laid, and the file’s current status (closed / inactive / open).

- Confirmation of what closing documentation exists (whatever it is called internally), and whether a redacted executive summary can be released.

CBC Ombudsman: unfair “limbo,” editor’s note, and expected follow-up

In February 2020, I filed a formal complaint with the CBC Ombudsman regarding the CBC coverage of this matter. That complaint was not a personal attack, and it was not written with the benefit of hindsight. It was a procedural objection raised in real time, while the case was still unresolved and no charges had been laid.

What my Ombudsman complaint actually raised

The complaint asked how fairness is preserved when a person is publicly named during an ongoing investigation, and what obligations exist when that investigation later concludes with no charges. It focused on process, safeguards, and outcomes, not on assigning motive or alleging criminal conduct by any journalist or institution.

In particular, the complaint can be summarized as having raised the following institutional questions:

- How does CBC ensure it does not interfere with an ongoing police investigation when reporting before charges are laid?

- What safeguards exist to prevent investigative timing or outcomes from being shaped by media disclosure rather than police process?

- How is fairness preserved when a person is named at the allegation or arrest stage, but the matter later concludes with no charges?

- What obligation exists to make the outcome as visible, durable, and discoverable as the original allegations?

These were not hypothetical concerns. They were raised precisely because at the time the outcome was uncertain, and because the reputational consequences of being named are foreseeable and long-lasting when no court process ever follows.

This complaint to the CBC Ombudsman noted that this case did not arise in isolation. I identified multiple CBC articles authored by Caroline Barghout in 2018 and 2019 in which individuals were named at the investigation or search-warrant stage, prior to any criminal charges being laid.

In several of those cases, no follow-up reporting clearly stating the eventual outcome was ever published, leaving the public record incomplete and the reputational consequences unresolved.

This pattern raised a broader concern: when naming prior to charges becomes routine rather than exceptional, the ethical burden to ensure durable, prominent outcome reporting becomes greater, not lesser. Absent that follow-through, the presumption of innocence is undermined not by a single editorial decision, but by the cumulative effect of allegation-stage visibility without outcome-stage accountability.

Ombudsman Nagler acknowledged that the CBC’s default editorial policy is generally not to name individuals prior to criminal charges being laid.

Ombudsman on default policy regarding naming

“The default position is not to use the name of the suspect in a case like [Richardson's]”

However, the Ombudsman characterized the decision to name Richardson prior to charges in this instance as a judgement call.

What Ombudsman Nagler addressed; What he did not

The Ombudsman reviewed whether CBC followed its internal procedures when deciding to name a person before charges were laid. On that narrow question, he concluded that the correct editorial approvals were obtained, concluding that Barghout and CBC management “all agreed that it was suitable”. An explanation for why they all concluded it was suitable to deviate from the default policy of the JSP on this matter was not provided.

However, several concerns raised in the complaint were not examined in substance, they can be summarized as follows:

- Whether a reporter's actions during an ongoing investigation can create procedural risk when the subject has not yet been questioned by police. (JSP: Constraints imposed by Law)

- Whether any safeguards exist to prevent investigative momentum from being altered once sealed material becomes public mid-investigation. (JSP: Constraints imposed by Law)

- Not only whether the absence of a durable outcome record leaves the public with an incomplete and potentially unfair or misleading understanding of the case, but also what editorial standards, review processes, and follow-up obligations the CBC applies to ensure that outcome reporting is fair, proportionate, and unbiased, particularly where no charges are laid, and where reputational harm may persist long after the initial publication. (JSP:Fair treatment and reporting of outcome, JSP:Privacy Principles)

Instead, Nagler's review accepted that journalism can sometimes prompt institutions to act.

Ombudsman on timing

“There are many instances in which journalism prompts those institutions to act, and justice is served when it might not otherwise have happened. ”

This passage from Ombudsman Nagler links media attention to institutional police action without clarifying how such dynamics should be constrained when charges are not authorized by the Crown, and no court adjudication occurs.

That timing is the core harm mechanism: publication occurred while the investigation was still ongoing, at a stage where the justice process had not produced a stable outcome the public could fairly rely upon.

Why this matters

An Ombudsman review that focuses narrowly on whether internal procedures were followed, without fully addressing outcome-level fairness, leaves the core harm unresolved.

The harm here is not theoretical. It is structural: a person was publicly named at the allegation stage; no charges were ever laid; and the absence of comprehensive outcome reporting allowed the allegation record to become permanent, while the outcome remained marginal.

Accountability is not satisfied by process alone. When public power is exercised, by police, by prosecutors, or by publicly funded media, it must be expected that the public record can be trusted to reflect the outcome with equal clarity.

One thing the CBC Ombudsman did agree on, was this need for more context upon conclusion.

Ombudsman on unfair limbo

“But to date, there has been no outcome for your father - his status is stuck in limbo. I think you are entirely correct in finding this to be unfair to him after this long a period of time. It should be made clear to the public that to this point, at least, the arrest has not led to any criminal charges. ”

A step in the right direction

“I believe that it is possible to acknowledge the strange circumstance here without doing an entire separate story. CBC could craft an editor’s note and apply it to the original article indicating that to this point no charges have been laid.”

Expected comprehensive reporting

“If and when the case does come to a definitive conclusion, I would expect CBC to report on that outcome in a more comprehensive way.”

That expectation matters because it describes what ethical, outcome-focused journalism looks like: if a story names a person at the allegation stage, it has a duty to report the outcome with comparable clarity and prominence, especially when the outcome is no charges.

Despite Nagler’s stated expectation, this comprehensive coverage never materialized.

CBC editor’s note: outcome acknowledged, prominence unchanged

Months after the legal matter concluded without charges and the Ombudsman expressed his expectation of more comprehensive coverage, the CBC did add an editor’s note to the original article. A note is better than silence, but it is not comprehensive follow-up reporting, and it does not correct the structural imbalance created when the original story remains highly discoverable while the outcome is not.

If the headline-level narrative is “arrest and allegations”, then the matching public-interest narrative should also be “no charges,” stated clearly and prominently, and supported by a significant update to the original article, that is itself still discoverable, shareable, and permanently linked to in web sources.

The editor’s note exists as an annotation rather than as a headline update, body-text revision, or standalone follow-up article, and therefore does not materially alter the article’s discoverability or summary context. As such, it does not satisfy the Ombudsman’s stated expectation for more comprehensive reporting at conclusion.

Outcome-level reporting should be routine, not remedial. Yet when Manitoba Prosecution Services decided not to proceed with charges, the Winnipeg Free Press, CTV, and other outlets offered neither an editorial note nor any further coverage to inform the public of that outcome. It should not require a formal Ombudsman complaint for outcome-level reporting to occur.

Questions that still require answers

This letter is directed at institutions that exercise public power. The standard is not “did we follow a procedure”, it is: whether the public record is fair, complete, and accountable when a person has been publicly named and no charges follow?

To the Winnipeg Police Service

- Will WPS acknowledge plainly that a sealing order expired during an ongoing investigation, after which the record became releasable and was obtained by media?

- Who was responsible for monitoring/renewing the seal, and what accountability exists when sealing protections lapse during an investigation?

- Why didn't the WPS question Richardson regarding this matter until the day after Barghout provided Richardson with details of the police investigation?

- What justified multiple arrests, and why were charges never authorized by the Crown? What changed between arrests, if anything?

- Why did a Winnipeg Police Service spokesperson publicly characterize this investigation as “complete” prior to the February 2019 CBC article being published, when no charges had been authorized by the Crown, a second production order was later sought in March 2019, and investigative steps clearly continued after that statement?

- What outcome/closure documentation exists, and can WPS release a redacted executive summary so the public record is not left to imply wrongdoing where none was proven in court?

To CBC News

- Why did Barghout and CBC Management (Melanie Verhaeghe and the Director of Investigative Journalism at CBC News) find it suitable to deviate from the default policy of the JSP and name Richardson prior to charges?

- Why did CBC News not report on the March 2019 production order, obtained after the initial coverage and before charges were expected, particularly given that the matter ultimately concluded with no charges being authorized?

- How did the CBC Ombudsman's expectation ensure the JSP Policy on "Fair Treatment and Reporting on the Outcome" in this matter?

- Why did the CBC not report on the outcome in a more comprehensive way as the Ombudsman said he would expect at definitive conclusion?

- What internal editorial standards or review criteria does the CBC apply when determining whether an outcome update should take the form of an editor’s note versus a substantive article update or follow-up story, and how were those criteria applied in this case?

- Will the CBC ensure that the definitive outcome of this case, no charges laid and no civil action, is displayed with equal prominence to the original allegations, including on initial page view and in metadata and social previews, rather than confined to a minimal editor’s note?

What accountability looks like

This letter is not asking the public to assume facts not in evidence. It is asking institutions to complete the record and accept responsibility for foreseeable reputational harm, where the outcome is clear: no charges.

- WPS must acknowledge the timeline surrounding sealing lapse, multiple arrests, spokesperson statement, and second production order plainly. Not as a vague “the record became public,” but as an accountable statement detailing the timeline of events: the seal expired during an ongoing investigation; after expiry the record became releasable; media obtained it; WPS later attempted re-sealing and this was denied; first police contact/arrest occurred the day following media contact; police conducted a second arrest; police claimed the investigation was complete and charges were expected; police later sought a second production order as a further investigative act after this statement.

- WPS must supply outcome-level clarity about the arrests. What justified arrest power, why charges were never authorized, and how WPS prevents a person from being left in permanent reputational limbo when the outcome is no charges.

- CBC must do more than an editor’s note. A one-line note is not comprehensive reporting. CBC should provide a comprehensive update to the original story, including details about how the investigation was still ongoing at the time of original publication, acknowledge the timing of media contact prior to police questioning and arrests, and state the fact no charges were ever authorized, and no civil action was taken against Richardson.

- Both institutions must ensure outcome visibility. The “no charges” outcome must be at least as visible, permanent, and searchable as the original allegation narrative.

Key principle

If an institution allows a person to be publicly branded at the “allegation” stage, it has an equal obligation to make the “outcome” stage durable and visible, especially when the outcome is no charges.

This obligation has not been met. Today, the absence of durable outcome reporting does not merely leave a gap in the historical record. It actively allows false allegations to persist, mutate, and be re-amplified through search engines and automated summaries. What follows is not an opinion or an edge case, but a real example of what a reader sees when institutional outcomes are not made as visible as the original allegations.

Conclusion: Accountability requires outcomes, not silence

This letter does not ask the reader to take sides. It asks something far more basic: that when public power is exercised, the public record must reflect the outcome with the same clarity and durability as the allegation.

In this case, the outcome is not disputed. No charges were laid. No trial occurred. None of the allegations were ever tested. No conviction followed. No civil action ensued. Those facts are confirmed by Manitoba Prosecution Services.

What remains unresolved is not guilt or innocence, but accountability. A sealing order expired during an ongoing investigation. Arrest powers were used. A person was publicly named. And yet, when the matter concluded without charges, no equally prominent outcome record was produced.

That gap is not theoretical. It has real consequences. In the absence of durable outcome reporting, allegations persist, and are re-amplified through search engines and automated summaries, even when they are false.

This record shows that arrests occurred, and even after expectations of criminal charges were documented, investigative steps continued, yet no charges were ever authorized by the Crown. Despite this outcome, the public narrative largely stopped at the point of arrest, with little explanation provided as to why the matter did not proceed.

The absence of follow-up reporting or accessible clarification has left an incomplete public record, one that continues to affect reputation without any corresponding criminal finding. This letter exists to document that gap and to ensure that the full investigative outcome is available alongside the initial coverage of the allegations.

Sources

- CBC article breaking the story, naming Ed Richardson prior to charges

- Hosted on CBC. Fairness, editor’s note remedy, and expected comprehensive reporting

- The original, unedited Arrest But No Charges Ombudsman review, hosted locally at /docs/2020-06-10-cbc-ombudsman-review-richardson.pdf

- Prior Ombudsman reporting on naming individuals prior to charges.

- Correspondence from MPS, Hosted locally at /docs/2025-12-16-manitoba-prosecution-service-letter-sealing-order-expiry.pdf

- Letter from Manitoba Justice noting charges were not authorized by the Crown in this matter, hosted locally at /docs/2023-10-04-manitoba-justice-fippa-charges-not-authorized.pdf

- Sealing order for the original production order, approved on the basis that disclosure would interfere in an ongoing investigation, hosted locally at /docs/2018-01-08-sealing-order.pdf

- The original production order, sealed, and then released to the media on Jan 25, 2019. Available on request from Judicial Authorization Registry

- A previously unreported second production order, requested after Richardson's arrests, and prior to his scheduled court date. Available on request from Judicial Authorization Registry

Primary-source grounding

The strongest claims on this page are anchored to the Manitoba Prosecution Services letter (mechanics of seal expiry / media access / attempted re-seal / “no charges were laid”), the WPS spokesperson quote regarding the investigation being complete before further investigative action was taken, and the CBC Ombudsman review (fairness, “limbo,” and expectation of comprehensive outcome reporting), as well as the two production orders sought by the Winnipeg Police Service in relation to this matter.

FAQ

- Was Ed Richardson ever charged with a crime?

- No. No criminal charges were ever authorized to be laid.

- Did the case go to trial or result in a conviction?

- No. There was no trial, no conviction, and no judicial finding of wrongdoing.

- Did any party commence a civil action against Richardson in relation to this matter?

- No. No civil action was commenced against Richardson in relation to this matter.

- What is the core issue this letter addresses?

- A sealing-order lapse made investigative records releasable during an ongoing investigation; A spokesperson claimed the investigation was complete, charges were expected. The public received the allegation moment, but not an equally durable, prominent outcome record when no charges were laid.

- What is this letter asking WPS for now?

- A written plain explanation of why multiple arrests occurred without charges being authorized, and an accountable explanation of how sealing was monitored and why the sealing order protection lapsed while the investigation was still ongoing.

- What documentation normally exists when an investigation ends without charges?

- In many Canadian police services, investigations that conclude without charges still generate internal closing documentation, such as a file disposition summary, supervisory sign-off, or internal closure report. These documents may not be public by default, but they typically record: the investigative scope, whether reasonable grounds were ultimately met, the reason charges were not authorized, the file’s final status (closed, inactive, or otherwise). This letter asks whether such outcome-level documentation exists in this case, and whether a redacted summary can be released so the public record does not imply wrongdoing where none was proven.

- Is this letter alleging misconduct by the Winnipeg Police Service?

- No. This letter does not allege criminal wrongdoing or improper motive by any individual or institution. It asks whether investigative materials, and sealing orders were properly managed in a way that is fair, complete, and proportionate to the public harm created when a person is named and later not charged. If the public record is accurate and complete, transparency should strengthen trust, not weaken it.

- Why does the timing between media contact and the first arrest matter?

- Timing matters because it affects fairness, investigative integrity, and public perception, not because it proves wrongdoing. In this case, a journalist contacted Richardson and read the entire recently unsealed police production order to him on February 8, 2019. Richardson had not yet been questioned by police regarding the matter and their investigation was ongoing. The following day, February 9, 2019, Richardson voluntarily attended police headquarters and was arrested. This sequence raises legitimate public-interest questions about investigative process and safeguards: why first police questioning occurred only after media contact, whether investigative steps were already complete prior to the arrest, how police ensure that media access to investigative material does not inadvertently shape investigative timing or outcomes. This letter does not allege coordination between police and media. It asks whether existing safeguards adequately protect investigative independence and fairness when investigative records become public during an ongoing investigation.

- Why raise these questions now, years later?

- The passage of time has not reduced the impact of the original reporting; the allegations remain searchable and prominent. The absence of a durable outcome record means the harm continues, even though the investigation concluded without charges. Accountability is not time-limited when reputational harm is ongoing.

- What standard applies when police action results in no charges?

- Police officers regularly ask civilians to account for their actions. Civilians are arrested, searched, terminated from employment, and publicly named based on investigative thresholds that fall short of proof. In this case, those powers were exercised. Yet when the outcome was no charges, no equivalent public accounting followed. This raises a basic accountability question: What standard applies to the police service itself when arrest power is used, a statement is given by a spokesperson, reputational harm occurs, and the file concludes without charges being authorized? If civilians are required to answer for suspicion, is it unreasonable to ask police to answer for outcomes?

This letter does not ask the public to infer wrongdoing by any institution; it asks those institutions to correct or complete the public record if any of the facts presented here are inaccurate or incomplete.

This letter is written in good faith, with one goal: to ensure the public record reflects not only allegations, but outcomes, especially when those outcomes involve no charges or civil action against the accused.

Authorship and independence note: This letter was written and published solely by Ed Richardson's son, Dave Richardson in his personal capacity. It was not written by, reviewed by, endorsed by, or coordinated with Ed Richardson. Ed Richardson had no prior knowledge of its publication and did not participate in, or support its preparation in any manner whatsoever. Nothing in this letter should be understood as a statement by Ed Richardson or as a disclosure of any confidential employment, settlement, or legal terms to which he may be subject. Ed Richardson cannot comment on any such confidential matters beyond what is already public.

Clarification (not affiliated)

dearwinnipeg.ca is an independent website and is not affiliated with, endorsed by, or connected to dearwinnipeg.com or any individual, organization, or campaign operating under a similar name.

This page is a personal public-record statement authored by Dave Richardson and concerns only the matters described on this site.

Dave Richardson

proud son, researcher, technology enthusiast, former public servant.

Contact: author [at] daverichardson [dot] ca